The Marine Corps expects new capabilities it is experimenting with as part of the force design to start coming online in 2023.

Marine Commandant Gen. David Berger is in the middle of the services’ Force Design 2030 effort seeking to retool the Marine Corps by divesting of older capabilities like Abrams tanks and increasing investment in anti-ship missiles and Light Amphibious Warships (LAW) to become lighter and more expeditionary-focused (Defense Daily, March 27, 2020).

“We’re rehearsing, we’re experimenting now in all parts of our Marine Corps. The capabilities that we need to acquire, they will begin to come online in numbers in late [2022], ‘23, ’24, ’25. But beginning in ‘23 really,” Berger said during a Center for a New American Security event on Tuesday.

Starting in 2023, “we’ll have the capability in the hands of the commanders that they need. Only limited by, if it’s a material kind of a thing, then by production and by resources.”

Berger noted the material equipment is just one part of the service changes.

“I think we’re rapidly changing the way that we manage our people and the talent and the way that we train. Because otherwise all the concepts and capabilities in the world aren’t going to work with the current systems that we have for how we manage our people and develop them and how we train ourselves.”

“Now my shoulder is into those two parts, the training part and the human part, to match the velocity with how we are adjusting our organization,” he continued.

Berger highlighted two capabilities he expects to start coming online in 2023: ground-based anti-ship missiles and the Light Amphibious Warship (LAW).

The first uses the Joint Light Tactical Vehicle (JLTV), takes the top off , makes it unmanned, and adds a missile launcher to target both maritime and land targets.

The JLTV is the replacement for the current Humvee.

“And there’s a number of these and they’re unmanned and one of them may or may not be manned as sort of a quarterback of these other ones. And you can move them around, you can position them where you want, they’re tied in together with your radars and your sensing systems and the threat now has to know you can hold their ships at risk and their ground forces too. We will have that capability in ‘23,” Berger said.

Last April, the Marine Corps conducted a successful live fire test with Raytheon Technologies [RTX] that launched a Naval Strike Missile from a modified JLTV against a sea surface target (Defense Daily, April 30).

Berger also said the Marine Corps will have the LAW “as fast as we can procure them” and advancements to the service’s radar systems are on the way as well.

“All these things are coming pretty rapidly.”

Berger said it is hard to put a value on new capabilities the Marine Corps does not have yet, like the LAW, but the standing force they are creating needs the ability to move around more easily from the sea.

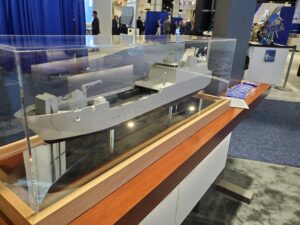

The LAW is intended to support the Marine Littoral Regiment by transporting up to 75 Marines at a time up to 3,000-4,000 miles while holding extra fuel and cargo. The Navy said it plans the vessel to be 200 to 400 feet long with some speed, draft and beachability requirements.

Earlier this year, Marine Maj. Gen. Tracy King, Director, Expeditionary Warfare (OPNAV N95), said the services were aiming to start research, development, test and evaluation on the LAW in one year and buy the first vessel by late fiscal year 2022, allowing time to begin exercises. The second LAW is aimed for the following year (Defense Daily, Jan. 14).

Separately, Berger said the inertia in the acquisition bureaucracy is the biggest impediment to changing the service, although some amount is needed.

“Our system…rewards continuing your program of record, whatever that is, if you’re involved in acquisition. Your whole life exists around modifying, continuing, getting more resources for my program of record so the system is not built in an agile manner to reward things that are moving at a higher kind of RPM. It wasn’t designed for that.”

Berger said this is not the fault of personnel who are lazy but a bureaucratic process “that was built for a different speed and in which you could take your time and develop something and four, five years later it would be ok to get it to the field.”

Now that pace is too slow and procuring capabilities like that means they are already obsolete when they are acquired.

“Our focus is on how do you move faster with the tools, the policy that you have. And Congress has given us some, we haven’t used all of it – I’m convinced we haven’t squeezed all we can out of it in terms of rapid acquisition, rapid testing,” Berger continued.

However, Berger also noted some degree on inertia is useful.

“If there was no resistance…we would probably leap left and right every couple of years chasing the next shiny objects. So some degree in there is healthy, it forces us to – do you have a compelling argument for this change that you’re arguing for. If you have it, then go. If you don’t, then I think that resistance helps make sure we don’t lurch from one side to another chasing sort of the shiny object of the moment.”

“Some degree of that is actually a good thing, but too much will definitely bring you to your knees,” he said.