ATLANTA–As the F-35 Lightning II Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) program moves from low-rate initial production into full-rate production, a top official with prime contractor Lockheed Martin [LMT] said on Tuesday the program’s focus shifts from initial development to sustainment and continuous capability development and delivery (C2D2) necessary to keep it relevant for decades to come. To that end, the company has about 60 software and hardware upgrades currently planned for the multi-role fighter over the next 10 years.

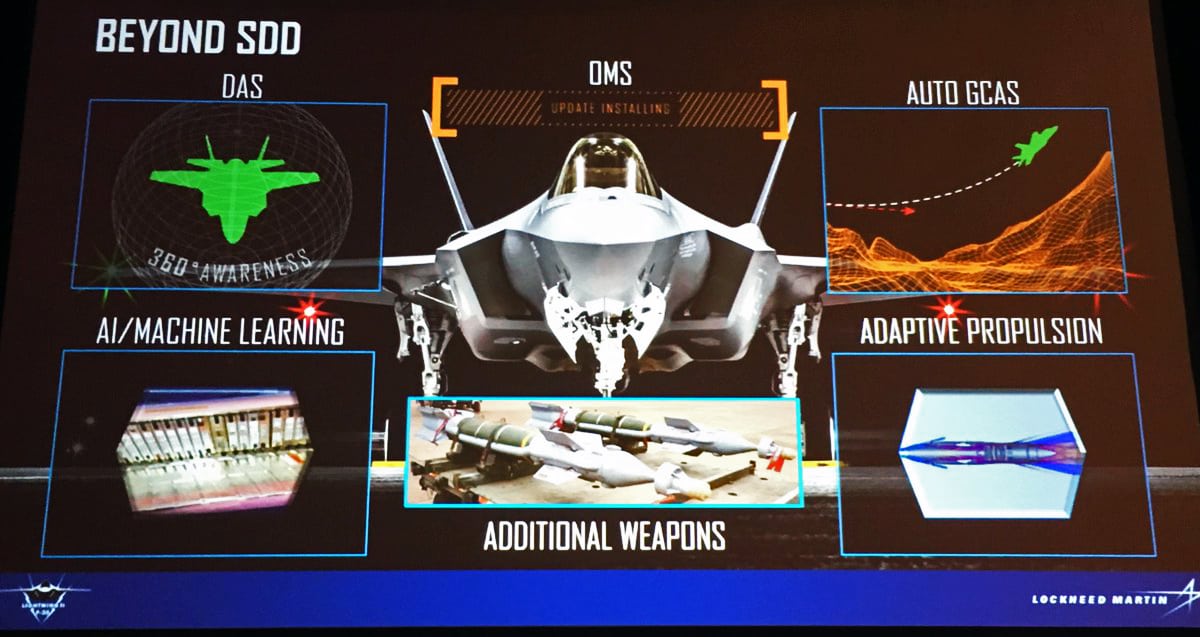

Speaking at an AIAA Aviation Forum here, Jeff Babione, head of Lockheed Martin Advanced Development Programs, better known as Skunk Works, said one of the most immediate upgrades coming to the F-35 is an automatic ground collision avoidance system (auto-GCAS), technology that didn’t exist yet when the F-35 was being built but has since been implemented on the F-16 and saved the lives of seven pilots by taking control to avoid a collision when the pilot was unable to do so.

In replacing Northrop Grumman’s AN/AAQ-37 distributed aperture system with one by Raytheon, Babione said the F-35 will gain around five times the resolution in its 360-degree sensor package at a lower cost. Further out, Lockheed Martin is seeking an increased integration of AI and machine learning.

In replacing Northrop Grumman’s AN/AAQ-37 distributed aperture system with one by Raytheon, Babione said the F-35 will gain around five times the resolution in its 360-degree sensor package at a lower cost. Further out, Lockheed Martin is seeking an increased integration of AI and machine learning.

The F-35’s hallmark is its powerful sensor suite, and one of the challenges is parsing, sharing and making use of the data it gathers. One possibility could be a future in which the only reality the pilot sees “out of the cockpit is one that is completely augmented,” constantly showing AI-recommended decisions, said Babione, who until recently was the F-35 program manager for Lockheed Martin.

Those changes will be part of the ongoing push for lower costs. To this point, depending on the variant, unit cost has decreased from close to $200 million to about $94 million, but Lockheed Martin promises an attractively priced $80 million fighter by 2020. At that point, production is slated to have ramped up to 150 units annually, compared to this year’s scheduled 91. By then, at least the U.S. Navy and the U.K. Royal Air Force should have joined the Air Force, Marine Corps and Israel in initial operational capability, Babione said.

The coming rampup in production to 150 units annually is important, because for the program’s eight partners and three countries with foreign military sales agreements – which Babione said could expand, as there are “three or four more” in negotiations – the F-35’s three variants fill a lot of roles, replacing everything from an F-16 to a Harrier Jump Jet to an F/A-18 Hornet or F-4 Phantom around the world.

The $325 billion JSF program’s footprint is so large that it would be the world’s 50th wealthiest country by GDP – comparable to Greece or the Czech Republic. That global supply chain that lets Lockheed Martin work on driving down the price is the mark of a modern large-scale program.

But the other side of building a fighter in the modern world, Babione said, is that there’s a massive amount of oversight and unit price isn’t the be-all, end-all anymore. Customers are thinking more than ever about sustainment cost.

“In an unprecedented way, Congress is looking at the cost to own the F-35 over its entire life-cycle,” Babione said. “Every building its built, every job that’s added to the U.S. Government, for 56 years. You think we thought about the total cost to own the F-16 when it started almost 50 years ago? Or the C-5 and the U-2 60 years ago? No. But that’s the new metric. So, what are we doing as an industry to ensure we reduce the cost to own?”