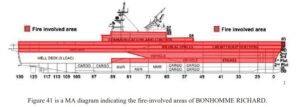

The Navy released a report this week reviewing the factors that led to the devastating five day fire that cost the service the USS Bonhomme Richard (LHD-6), an assessment showing that a range of failures at various levels were responsible for the Navy losing the $2 billion ship.

Former U.S. 3rd Fleet commander Vice Adm. Scott Conn oversaw the Command Investigation and his report found that “although the fire was started by an act of arson, the ship was lost due to an inability to extinguish the fire.”

Conn wrote that during the 19 month period executing LHD-6’s maintenance availability, repeated failures led to an accumulation of “significant risk” and an inadequately prepared crew that led to an “ineffective fire response.” He found four key focus areas that led to the outcome.

First, the report found that throughout the maintenance period, the material condition of the ship “was significantly degraded, to include heat detection capability, communications equipment, shipboard firefighting systems, miscellaneous gear clutter, and combustible material accumulation.”

It noted on July 12, 2020, the day of the fire, 87 percent of the ship’s fire stations were in inactive equipment maintenance status.

Moreover, the training and readiness of the ship’s force was “marked by a pattern of failed drills, minimal crew participation, an absence of basic knowledge on firefighting in an industrial environment, and unfamiliarity on how to integrate supporting civilian firefighters.”

Conn also said the integration and support expected by the shore establishment did not adhere to required standards. The Southwest Regional Maintenance Center (SWRMC) did not meet fire safety requirements and thus did not communicate risk to leadership “while facilitating unmitigated deviations from technical directives.” Also Naval Base San Diego (NBSD) did not ensure its civilian firefighters were familiar with Navy vessels on the base, verify they were trained to respond to a ship fire or effective practice how to support a ship’s force.

The SWRMC was the point of contact responsible for planning, execution and close out of maintenance actions while NBSD was responsible for ship support and associated maintenance activities while LHD-6 was moored at Pier 2.

The final factor was ineffective oversight by commanders across organizations that allowed subordinates to take “unmitigated risk in fire preparedness.” The report said a main source of the problem was a lack of codification of the roles and responsibilities expected by each organization in their oversight execution.

Pacific Fleet commander Adm. Samuel Paparo endorsed the investigation in an Aug. 3 letter.

He wrote that the material condition of the ship left it unnecessarily vulnerable to fire. “The training and readiness of the ship’s crew were deficient. They were unprepared to respond. Integration between the ship and supporting shore-based firefighting organizations was inadequate.”

“Finally, there was an absence of effective oversight that should have identified the accumulated risk, and taken independent action to ensure readiness to fight a fire. Common to the failures evident in each of these broad categories, was a lack of familiarity with requirements and procedural noncompliance at all levels of command,” Paparo continued.

Conn said all four focus areas included a lack of familiarity with important policies and requirements plus “procedural non-compliance at all levels of command from the unit level to programmatic, policy, and resourcing decisions.”

The report used the ship’s Aqueous Film Forming Foam sprinkling system as an example of how these areas combined led to unacceptable risk.

“Despite undergoing an availability, Bonhomme Richard was equipped with extensive shipboard firefighting systems, which included firemain and Aqueous Film Forming Foam (AFFF) sprinkling systems and hoses. At no point in the firefighting effort were any of them used, in part because they were degraded, maintenance was not properly performed to keep them ready, and the crew lacked familiarity with their capability and availability.”

The report also noted many requirements developed and codified in a report following a 2012 fire aboard the Virginia-class submarine USS Miami (SSN-755) were not properly executed. That fire also led to the vessel being lost while undergoing a maintenance availability.

“The considerable similarities between the fire on USS Bonhomme Richard (LHD-6) and the USS Miami (SSN-755) fire of eight years prior are not the result of the wrong lessons being identified in 2012, it is the result of failing to rigorously implement the policy changes designed to preclude recurrence,” Conn wrote.

The report said the non-nuclear surface fleet was on a “trajectory of an unacceptable fire prevention and response posture with a high level of accumulated risk before the fire started on 12 July 2020.”

“Once the fire started, the response effort was placed in the hands of inadequately trained and drilled personnel from a disparate set of uncoordinated organizations that had not fully exercised together and were unfamiliar with basic issues to include the roles and responsibilities of the various responding entities,” Conn said.

Several Congressional leaders expressed strong disappointment and vowed congressional investigations and pressure to fix the causes.

“The loss of the USS Bonhomme Richard was a completely avoidable catastrophe. Although the blaze was started by a disgusting act of arson, this was a manageable fire that consumed a multi-billion-dollar asset due to systemic failure and disregard for basic safety protocol. Today, I read the investigation with shock and anger. Once again, an avoidable military mishap occurred because of a low level of readiness, multiple training issues, and failures at ‘all levels of command,” Rep. John Garamendi (D-Calif.), chairman of the House Armed Services Subcommittee on Readiness, said in a statement Tuesday.

Garamendi vowed to “immediately begin investigating this matter to determine the full extent of the negligence and complacency that occurred and enact meaningful changes to transform the culture of neglect into a culture of safety throughout the Navy.”

House Armed Services Subcommittee on Seapower and Projection Forces Chairman Rep. Joe Courtney (D-Conn.) added that “based on the initial reading, this three-billion-dollar loss to the American taxpayer was largely preventable if the Navy and their private contractors had even a bare level of training and the necessary equipment to combat the blaze—one of the tragic lessons the Navy should have absorbed from the Miami fire nearly a decade ago.”

“As it stands, however, we learned that it took two full hours for the first drop of liquid to begin suppression—a stunning revelation that now requires extensive oversight, which we intend to conduct immediately,” he continued.

Rep. Rob Wittman, (R-Va.), ranking member of the Seapower subcommittee, said the fire did not have to lead to a “major loss,” but no sense of urgency early in the fire combined with “negligent attitudes towards cleaning, preservation, and stowage, degraded operability of core fire-fighting systems, and insufficient resources, and you lose the ship.”

Wittman underscored the importance of losing LHD-6 amid competition with China.

“This isn’t just one step backwards – this is a faceplant. For every deckplate leader, let this be a wake-up call: those seemingly mundane tasks come from lessons learned in sweat and blood. To have to relearn this lesson is unacceptable,” he continued.

Ranking member of the Senate Armed Services Committee Sen. James Inhofe (R-Okla.) agreed that the Navy must take immediate and comprehensive action, but saw it as an additional reason to expand shipbuilding facilities.