The Navy Department’s latest 30-year shipbuilding plan has three alternative scenarios for the service’s acquisition and inventory of battle force ships, with two reflecting a budget with “no real growth” and the third with $75 billion in real growth.

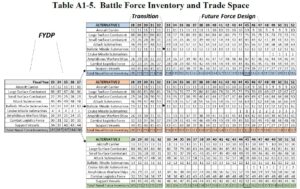

In the plan, the first two lower-range options have no additional budget growth, resulting in a total battle force inventory of 316 and 327 battle force ships by 2052, respectively. The third highest range option would have the Navy reach 326 ships by the mid-2030s and 367 ships by 2052.

This report said the first three options “assume industry produces future ships on time and within budget,” while the highest range option represents adding $75 billion real growth beyond the five year Future Years Defense Program (FYDP) in FY2022 constant dollars.

The Navy said the largest plan is informed by industrial base capacity and on-time and on-budget performance to achieve “326 manned battle force ships in the mid-2030s, and ultimately achieves 363 manned battle force ships in FY2045.” The high range plan ultimately reaches 367 ships by 2052.

2045 was the timeline former Secretary of Defense Mark Esper used for his shipbuilding planning during the Trump administration, outlining options for a 500-ship fleet within decades in a proposals called Battle Force 2045 (Defense Daily, Oct. 6, 2020).

Splitting the 30-year shipbuilding plan into three options is a departure from past plans that decided on a single Navy plan, with the Navy explaining this choice by underscoring predictions past 10 years are difficult.

“Evolving operational concepts and rapid technological changes make single-point predictions after approximately 10 years unreliable. Accordingly, [the plan] highlights a potential range of options for key fleet platforms beyond 10 years,” the document said.

“As the Administration works with Congress to refine future years’ plans, the composition and ramp-up of battle force procurement beyond FY2028 will be adjusted accordingly. Consistent with the FY2022 shipbuilding plan approach, combat effectiveness and industrial base production feasibility were taken into account,” it added.

The three options all share the same FYDP, then start to diverge over FY ‘28-’32 in a period the Navy calls “transition” before moving to the “Future Force Design” running from FY ‘33 – ‘52.

After the FYDP, the first two plans do not consistently procure at least two large surface combatants and two small surface combatants annually until possibly the mid to late 2040s. In contrast, the third plan with boosted funding maintains at least two ships annually for large and small surface combatants and in several years would procure three larger surface combatants.

Similarly, the first two plans do not consistently procure at least two attack submarines per year. The first alternative occasionally has the Navy procure one submarine per year by 2047, while the second plan exclusively procures two or three attack submarines starting in 2034. The third alternative maintains two attack submarines procured per year through 2052.

A note in the document said the ability of the industrial base to support alternative three “has not been independently assessed.”

All three plans also maintain the same procurement schedule for new ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) with the new Columbia-class (SSBN) vessels.

The Navy reiterated its procurement priorities, including the Columbia-class SSBN, readiness to deliver a combat-credible forward force in the near-term, invest in increased lethality and modernization with the best potential to deliver non-linear warfighting advantages vs. Chia and Russia in the mid-to-far term and grow warfighting capacity reflective of the 2022 National Defense Strategy.

“The once in a generation recapitalization of the Nation’s most survivable leg of the nuclear triad comes at the same time as the Navy modernizes for future threats, placing strain across the Navy’s budget. The Navy will only grow ready, lethal, and survivable warfighting capacity at a rate supported by the fiscal guidance and our ability to sustain that capacity in the future,” the Navy said.

Moreover, the document said the plan “does not resource capacity beyond what can be reasonably sustained – manning, training, maintenance, ordnance, operations, and future modernization. However, some risk was accepted in ship maintenance and readiness accounts. Although relatively small, any shortfall in maintenance will be realized as additional cost in the out years with growth above what is not funded in the current year.”

The Navy said without any real budget growth the two lower end ranges do not procure all platforms at the desired rates, noting that is two ships per year for destroyers, attack submarines, and frigates.

The document said “industry needs to demonstrate the ability to achieve” that rate of two ships per year, but the plans still maximize capabilities within projected resources, industrial factors, and technology constraints for a capable force.

“Overall, this approach accepts risk in capacity in order to field a more capable and ready force,” the document said of the first two lower end options.

This is the first detailed 30-year shipbuilding plan since the final Trump administration document, released 10 months late in December 2020 (Defense Daily, Dec. 10, 2020).

The Biden administration’s first long-range shipbuilding plan was an abridged version, released last June, without detailing clear plans past FY ‘22. That plan only listed a potential range of naval platforms, for a range of 321 to 372 manned vessels going out 30 years (Defense Daily, June 21, 2021).