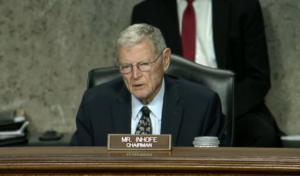

The chair of the Senate Armed Services Committee used a Thursday nomination hearing to spotlight his opposition to House legislation that would made it harder for the Department of Energy to collaborate with the Pentagon on future nuclear-weapons budget requests — something, he believed, that “some people ... in the Department of Energy” would like. From the dais, Sen. James Inhofe (R-Okla.) blasted these unidentified officials for embracing the policies advanced by the House — policies Inhofe said would prevent…

By

By