The Assistant Commandant of the Marine Corps this week explained why the Light Amphibious Warship (LAW) capabilities are needed and what the service hopes to learn from experimenting with commercial vessels while procurement was delayed three years.

The LAW, also referred to as Landing Ship, Medium, “is absolutely required, up to 35 of them. Those vessels enable the three littoral regiments in the Pacific to move tonight, to immediately move to strategic choke points and strategic locations throughout the battlespace before the action begins in order to conduct sea denial, as part of distributed maritime operations,” Gen. Eric Smith said during the Defense News Conference on Sept. 8.

He noted the LAWs have to be beachable rather than require certain kinds of ports of draft requirements to add flexibility and defense.

“Because when you open up the entirety of a coastline, now you’re harder to find. If you just say, hey, you got a 32 foot draft – well, there’s about six places that the adversary has to target to take that away from you.”

While the LAW was originally planned to start procurement in fiscal year 2022, the Navy’s FY ‘23 budget request said the service was pushing procurement of the first vessel back three years to FY ‘25. The second vessel will then be procured in FY ‘26 followed by two more in FY ‘27 (Defense Daily, March 30).

Smith admitted the delay of LAW is both hurting the Marine Corps but also allows it to mature how to use the vessel and what capabilities it will need.

“Anytime you say delay – delay for us as risk and as the force provider, or Commandant as a Title 10 holder, that risk gets passed on to combatant commanders. So when you don’t have that Light Amphibious Warship, for an additional year, that risk is absorbed by the combatant commander in the execution of [operational plans],” he said.

Smith also said delaying the LAW is a factor in first mover advantage, because the military wants to set the adversary off balance. He said given China is the pacing threat, the Marine Corps is looking at it as the potential adversary to plan against.

“You want to take advantage of opportunities with allies and partners to reassure, to reinforce, to train. You want to get out there and catalog during peacetime what they do, where they do it, how they do it. And the Light Amphibious Warship brings all those things – it can bring the Naval Strike Missile, can bring the [AN/TPS-80 Ground/Air Task-Oriented Radar (G/ATOR)], it can bring refueling, it can bring deception, it can bring strike.”

“You want that out there today because that causes a change in behavior today. If you don’t get it until next week, you absorb the risk for another week,” he continued.

Earlier this year, the Marine Corps said while it waits for the delayed LAW, it will explore a family of systems bridging plan to use Expeditionary Transfer Dock ships (ESB), Expeditionary Fast Transport ships (T-EPF), Landing Craft Utility vessels (LCU), and leased hulls to provide a basic level of mobility, experimentation and training (Defense Daily, May 11).

“Although not optimal, such vessels will provide both operational capability and a sound basis for live experimentation and refining detailed requirements for the LAW program,” the Marine Corps’ Force Design 2030 annual update said on May 9.

In May, Lt. Gen. Karsten Heckl, Deputy Commandant for Combat Development and Integration, said the service had already contracted with a commercial Stern Landing Vessel (SLV) provider, Hornbeck Offshore Services, to start experimenting with LAW concepts starting this summer or fall. The SLV is due to deploy to Hawaii to work with the 3rd Marine Littoral Regiment.

At the time, Heckl said the Marine Corps SLV contract included options to lease to more vessels while five companies conduct prototyping work on their LAW offerings.

Smith also explained what the Marine Corps hopes to learn from experimenting with the SLV as it finalizes the LAW.

“What we expect from them is how’s the loadout? What is your ability to move from point A to point B? What is your ability to hide yourself electromagnetically and physically? How quickly can you onload and offload? What do you do to connect fuel when you need fuel from a different source…What did you forget to bring with you? What did your supply chain look like? And can you use that vessel to both support you for organic mobility and can it be used for periods of time to support the joint force logistically?”

Smith noted the primary purpose of the LAW is organic mobility for Marines in the Marine Littoral Regiments (MLR).

So that’s what we’re going to be focused on in that experimentation period, as we put the first Light Amphibious Warships on the street.”

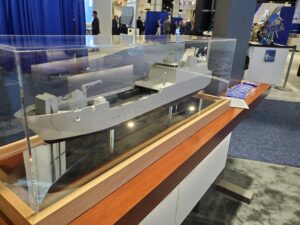

The LAW is expected to be 200 to 400 feet long, able to transport up to 75 Marines and their gear each, travel at least 3,500 nautical miles, carry up to 10,000 square feet of cargo to support MLRs, and have a crew of up to 40 Navy sailors.

The Marine Corps’ plans are committed to the LAW class on top of its requirements for 31 traditional larger L-class amphibious ships like the America-class Amphibious Assault Ship and San Antonio-class amphibious transport dock ship.